Archives

| May 19, 2002

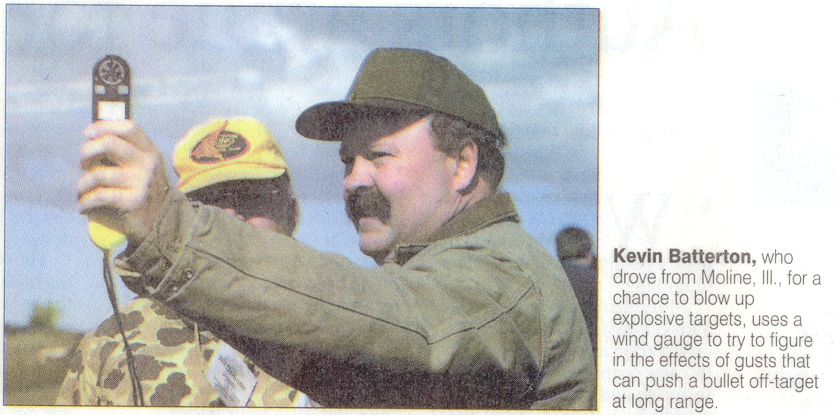

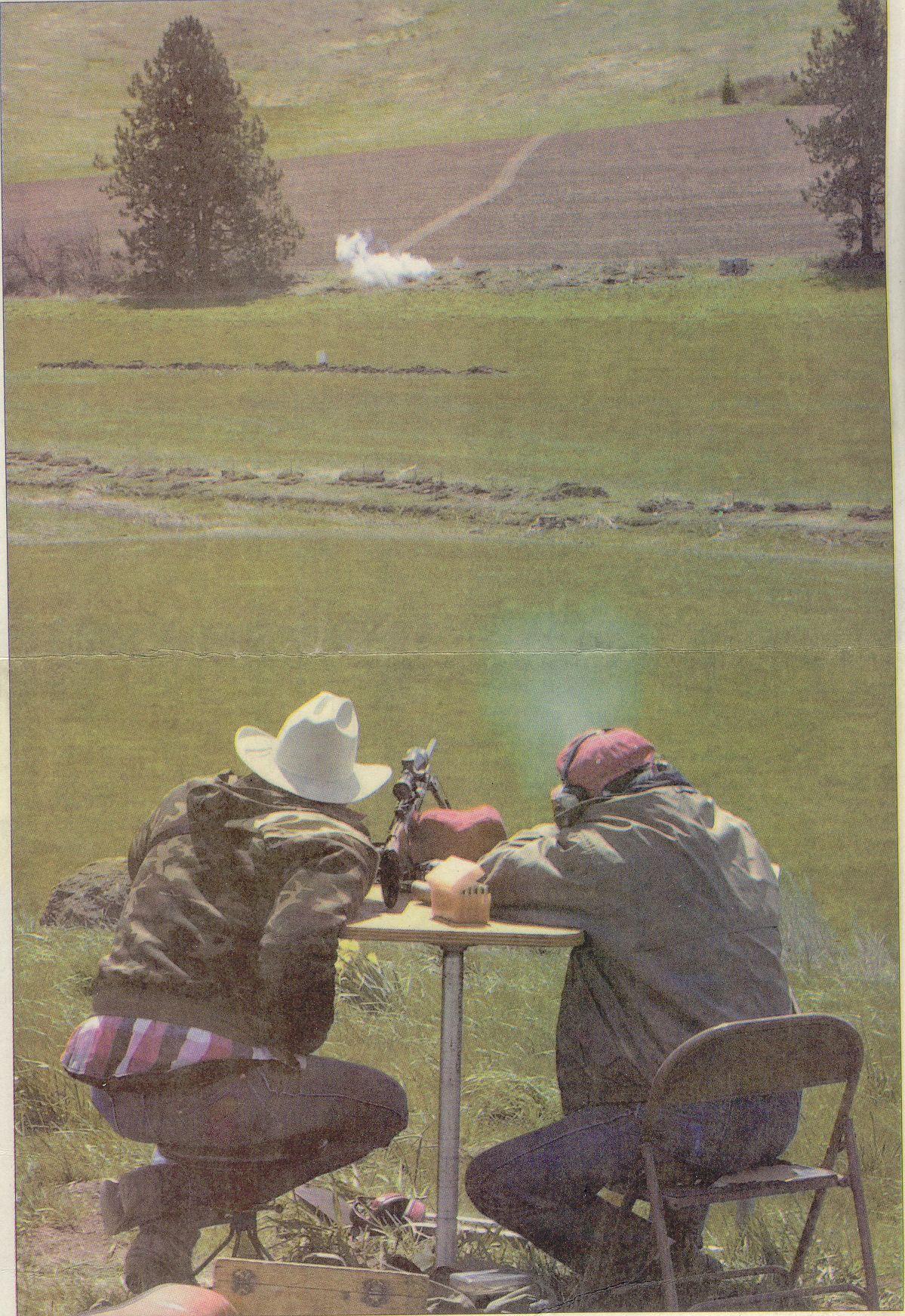

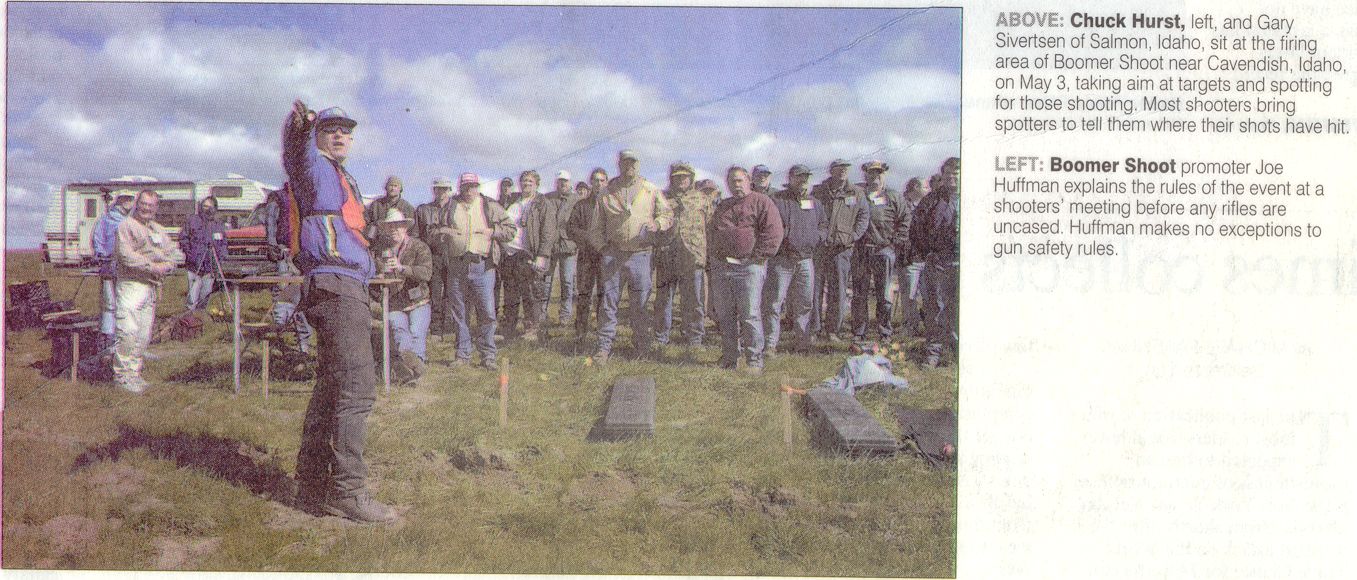

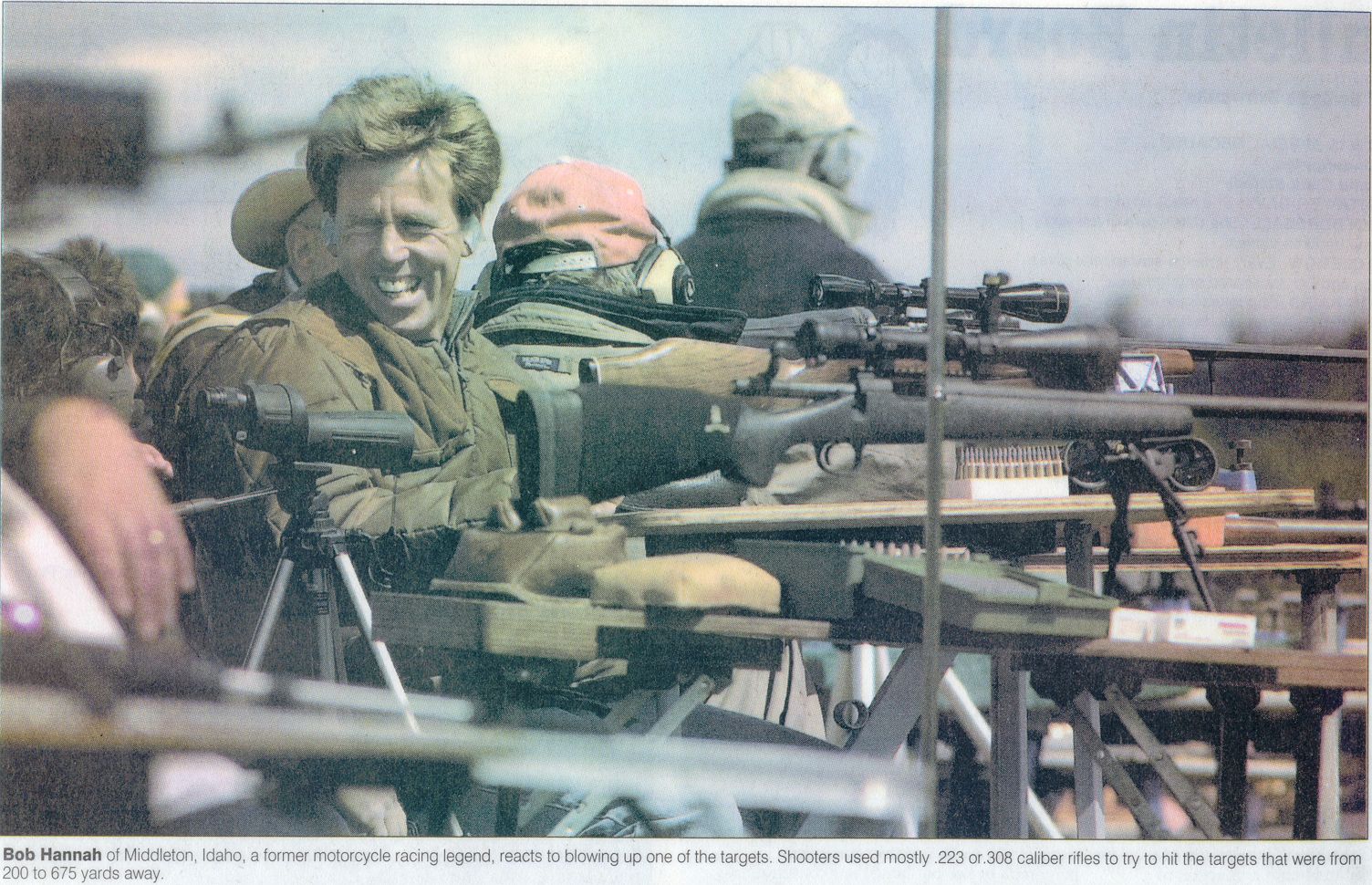

Things that go boom By VINCE DEVLIN of the Missoulian A farm in Idaho gives people a shot at some explosive fun CAVENDISH, Idaho - From as far away as California and New Jersey, on yet another day when spring can't seem to find its footing, about 50 people have gathered on a hill, in a field a few miles south and east of this otherwise quiet town, on the first Friday of May. But Alan Deyo, who lives in nearby Orofino, has only driven a few miles to the site. "I couldn't, for the life of me, figure out what was going on," he says. "So I asked around. Then I had to see this for myself." Deyo was working about nine miles away, on the far side of Dworshak Reservoir, last year when he heard the explosions. One, then another. Five, then six. Fifty. Sixty. A hundred. And more. All day long, it sounded like bombs were being dropped, or entire mountains dynamited, in the distance. And so Deyo has come to see what caused all those explosions. And what has he found? The director of a nonprofit Shakespearean theater company, that's what. Robert Bethune has traveled to Idaho from Ann Arbor, Mich., to blow things up. There's also a retired oral surgeon from Las Vegas. A farmer from Moline, Ill. A candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives from Chicago. A couple of retirees from Salmon. From across America, from all walks of life, they have gathered in a farmer's field to shoot guns at explosives. What's the attraction? "What's not to like?" says Rolf Nelson, a "semi-retired" Microsoft employee from Redmond, Wash. "It's like mixing the Fourth of July, hunting and friends." "This is wild," Deyo says. This is the Boomer Shoot. This is Joe Huffman's magic kingdom. The shooters are itching to get their guns out, but must wait for Huffman to call things to order and remind them that his safety rules will be rigorously enforced. Huffman, who lives in Moscow and also works for Microsoft, puts on the Boomer Shoot. He saves his family's empty cartons, and swings by a Moscow elementary school to grab the empty milk and apple juice cartons that the kids go through. It's his recipe - honed after a couple years of experiments with everything from diesel to Coleman lantern fuel - of ammonium nitrate, potassium chlorate, nitromethane racing fuel and baking soda, that will fill the cartons. The containers, ranging in size from 200 milliliters to one liter capacity, are then sealed, strapped onto stakes with rubber bands, and placed in a field on the farm owned by Huffman's father and two brothers. The smallest targets are closest, about 200 yards down from the knoll where the shooters sit at tables or lay on the ground in one long line. The target size is akin to folding a dollar bill in half and placing it two football fields away. More targets are 285 yards away, and more still at 350, 525, 550 and 675-yard distances, the latter near the top of a hill across the way. In all, about 300 targets are scattered in the field and up on the hill. They will not all be exploded by the end of the day. Precision rifle shooting is not an easy sport, and an unrelenting and bitterly cold wind will make it even trickier to put a bullet through an 8-ounce milk carton at such a distance. At 9 a.m. Huffman gathers the shooters together to run through the safety rules they've already read. (Rule No. 2, for example, goes like this: "There are no exceptions to any of the Minimum Gun Safety Rules. There have been people that thought that just because their firearm was unloaded, the bolt was removed, or had a 'chamber open flag' in it that the safe direction rule did not apply. There are NO exceptions. Yes, this rule is redundant. No, I don't care. Yes, I'm acting like a Nazi. No, I'm not going to change my mind. If you persist in prolonging this discussion, yes, you can have your money back. No, you will not be allowed to come back next year. Yes, we are very creative in making our own entertainment around here. No, they did not make the movie 'Deliverance' near here. Yes, they could have learned a thing or two had they done so.)" Huffman explains to the shooters that they are on a farm, not a gun range, and the usual 170-degree range where a gun can be pointed safely is more like 90 degrees here. There are farm houses visible to the shooters' left and a trailer behind and to their right. More homes are over the hill; it's important that no shots clear the top. A horn has been wired to the battery of Huffman's truck. One blast on the horn means stop shooting (most likely because a car is driving down a county road a couple hundred yards away). Two shorter blasts means shooting can resume. Huffman has a crew stationed on the road to watch for traffic and more patrolling the shooting area to watch for safety violations. The crew communicates via walkie-talkies strapped to their sleeves. "A dog shows up every year and runs around out on the range," Huffman tells the entrants. "Do not shoot the dog. We will sound the horn, wait for the dog to leave, and if he doesn't, we'll take the four-wheeler down there and chase him off." With a final warning not to shoot at road reflectors - "They don't make big booms anyway," Huffman says - the shooters retire to their stations to uncase their rifles, the majority of them Remington 700s, either .223s or .308s. Huffman gives two short blasts on the horn, and firing commences. Stephanie Sailor, 28, says her heart is in Chicago, but her neighborhood is not a safe one. She says she's been shot at once, twice had her home broken into and was once assaulted. After the assault she enrolled in a self-defense class where she was taught how to disarm an attacker. "Then it occurred to me that I wouldn't know how to use it if I did disarm someone," she says. So she enrolled in a gun class. Within 18 months she was a certified firearms instructor, in a city with some of the most restrictive gun control laws in the country. "I've been at anti-gun rallies where Mayor Daly has spoken, and I noticed he has armed guards on both sides of him," Sailor says. "It's illegal to keep a handgun in your own home in Chicago. City aldermen are allowed to carry handguns for their own protection, but regular citizens are not. It's just ridiculous. Why can the politicians protect themselves, but we can't?" The more Sailor learned about guns, the more she learned about gun control, and the more involved she got. Two years ago she ran for the U.S. House of Representatives on the Libertarian ticket in Illinois' Fourth District. Accepting only enough contributions to purchase computer equipment to run an Internet campaign, she says she got 12 percent of the vote. This year she's running in the Ninth District, against incumbent U.S. Rep. Janice Schakowsky, D-Ill. There is no candidate for the Republican nomination. "You go to vote, and there's only one person to vote for?" Sailor says. "That didn't seem like America to me." With the computer equipment purchased, she accepts no campaign contributions, and tells potential donors instead to give money to their favorite charity, "which is in line with Libertarian ideals anyway," she says. "I figure even if I don't win I will have done more for people than most politicians." Her involvement in politics, firearms and the Libertarian movement led her to a gun rights policy conference, where she met Huffman, who told her of the Boomer Shoot. She's on her second trip to Idaho to blow things up. "Who doesn't enjoy a big bang?" Sailor says. "Who doesn't like the Fourth of July? This is good, clean fun." Eight shots are fired before the first explosion. Someone has nailed one of the targets halfway up the hill in the distance. There's a BOOM, and a cloud of blue-gray smoke is quickly carried away by the wicked wind. A cheer rises from the line of shooters, who then hunker back down to aim at the tiny targets. Most of them have brought spotting scopes, and spotters who tell them where their shots have hit ("About an inch high, maybe an inch and a half to the right," one tells his shooter). Many take turns shooting. It costs $40 for a day of shooting at the three-day event (Saturday is mostly devoted to a long-range shooting clinic), but one station can add up to two more people at $25 apiece. It takes more than eight shots before another target explodes. Soon the booms blend into something of a rhythm with the gunfire. As the morning wears on, some complain that they're hitting targets that aren't exploding. Some guess the cold temperatures are affecting Huffman's recipe. At the lunch break, Huffman goes out to inspect the targets. "It's not as bad as I expected," he tells them when the shooters reconvene before the afternoon blasting begins. "Some of the targets have been nicked in the corners. There were others where the stake was hit and sent the target flying. There are only about 20 that didn't go off." Rolf Nelson says he's hit two dead on with his .223 that haven't exploded. "Time to drag out the heavy artillery," he says, disappearing back into the lines of trucks and cars. A couple of minutes later he appears with a large gun case, from which he extracts a Barrett 82A1 semi-automatic equipped with a muzzle break, to shoot .50-caliber Browning machine gun cartridges. "Those things are the size of bananas," says Alan Deyo, eyeing at the ammo. Nelson sets up in what the shooters call "the ghetto," which means leaving the area that's roped off for shooters and moving down the hill by his lonesome. Nelson lays on his belly and takes aim at a small outcropping of rocks 400 yards away. He fires a round, and - with the muzzle break venting the gasses sideways, laying the grass flat in both directions - the report is actually louder than some of the exploding targets in the distance. In the shooting area, people ask Nelson to move even farther away. He obliges. Soon, he's shooting tracers and a crowd is gathering. "Want to try it?" he asks. "The safety's right where your thumb'll be." The recoil is not as bad as one might expect, more a push than a kick, thanks to the muzzle break. But don't get too close to the scope, he warns, or you'll have an imprint of the scope's eyepiece between your eyes. Scott Clemenson of Pasco, Wash., takes a test drive of the Barrett's trigger. "I've gotta get me one of these," he hollers at his wife, Jera, after taking three shots. The line to try the gun grows. Huffman knows of only one other event like this, in Colorado. People travel thousands of miles to Idaho to shoot at the explosive targets because they can't do it where they're from. "Do this back home, you'd end up in the hoosegow," says Kevin Batterton, a farmer from Moline, Ill., with a laugh. Batterton is one of the more elaborately equipped shooters here, right down to the flip-down eye patch attached to the left lens of his glasses. In addition to his rifles and scopes and a wind gauge, he has a large laser range finder that'll tell him, within a yard, a target's distance. On a tripod behind him is a powerful pair of binoculars for his spotter, a telephoto lens and adapters that let him use the lens with a video camera that's also on the tripod, so he can record any hits and explosions he gets. There's clearly plenty of money invested in his gear. The laser range finder alone must have cost a bundle. "You don't want to know," Batterton says. "Heck, I don't want to know." Down the row, right-handed Chuck Hurst and left-handed Gary Sivertsen of Salmon, Idaho, share a table and never have to get up and change seats, whether they're shooting or spotting. "This is fun," says Sivertsen, who's shooting a Mexican Mauser .308. "It blows up when you hit it. Besides, I didn't want to cut the grass today, anyway." How many targets has he detonated? "Didn't come to keep score," Sivertsen says. "Just came to have fun." A few yards away Dr. Gerry Hanson, a recently retired oral surgeon, and Gary Gabbard, a retired airline pilot, are among the last to fold up shop several hours after the shoot started. Hanson flew the two of them up from Las Vegas in his private plane, and battled the same winds in the air Thursday that have challenged the shooters on this Friday. "I think half of Washington blew into Idaho yesterday," Hanson says, "and we just blew in with it. We had 45-knot winds. The landing was a handful. But it's been worth it." "You haven't lived 'til you've done this," says Lynn Martin of Anaheim, Calif. "Especially with the laws in California, we get out every chance we get to do this kind of stuff." Martin says most shooting ranges in Southern California are indoors, and the few outdoor ranges he knows of don't go beyond 300 yards. Huffman got a taste of shooting at explosives at the now defunct Blanchard Blast in Blanchard, Idaho, in 1996 and '97. There, the targets were pop cans stuffed with dynamite and placed 300 to 1,000 yards from the shooters. "My two oldest kids went up with me, and we said, 'We have to do an event like this ourselves, it's so much fun,' " Huffman says. "It took awhile to come up with an explosive mix I was satisfied with," he says. "You can use dynamite, but it's expensive, there's a lot of red tape, you have to get an endorsement on your driver's license to transport it, so we made our own material." In 1998 Huffman staged the first Boomer Shoot, an invitational in which he invited 10 shooters, and seven showed - five of them members of the Microsoft Gun Club. The next year he opened it up to the public and 25 people came. He held a second shoot in the summer that year that included a target with five times the explosive material of the normal ones. Its detonation brought people from miles around to see what had happened. The day after that shoot, while Huffman and his wife were traveling to Glacier National Park, some explosive liquid that had spilled on the ground spontaneously combusted and started the hayfield on fire. Huffman canceled a third shoot scheduled for '99. Since 2000 the event has been limited to the spring and has filled up quickly, even since Huffman expanded it to a three-day affair. Bethune, the director of the Michigan Classical Repertory Theatre, came across the Boomer Shoot while searching for precision rifle shooting events on the Internet. "The chance to shoot at a reactive target?" he says. "I figured, this has got to be fun." "It's so much better than paper punching," says Nelson, the fellow with the .50-caliber ammo who, like the others, shoots at paper targets most of the year. "Precision shooting combines both mental and physical aspects. Shooting a milk carton that's 600 yards away is not easy to do." Huffman's only requirement for shooters - besides that they adhere to his rules or hit the road - is that they have Internet and e-mail access. He's not interested in going to the post office to communicate with those who register. At his Web site - http://www.boomershoot.com/ - you'll find tons of information about the event, along with a Huffman quote: "As with some other things that are beyond what our ape-like evolution prepared us for," Huffman wrote, "explosions are, at some level, very odd and curious things. Our brains are programmed to pay special attention to strange and unusual things - 'magic' things. Explosions invoke that curiosity of magic in our brains. A gun with its 'action at a distance' capability is a magic tool. But at long distances there typically isn't the immediate confirmation that something really happened 'out there.' I change that. By creating a sort of Walt Disney like world where 'magic' happens I give the shooter an escape from reality. This is a Magic Kingdom for long range shooters. For one day I give them the keys to the Kingdom where they get to perform their own magic." Reporter Vince Devlin can be reached at 523-5260 or at vdevlin@missoulian.com |